I remember the first time I encountered an attractive fat woman in a fantasy novel. My heart flipped a little as I read about a woman was for-real fat. She wasn’t your usual fictional overweight woman, either: there was no zaftig or curvy or voluptuous to be found near the Scientist’s Daughter in Haruki Murakami’s Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. But she was definitely attractive. The narrator describes her as follows:

“A white scarf swirled around the collar of her chic pink suit. From the fullness of her earlobes dangled square gold earrings, glinting with every step she took. Actually, she moved quite lightly for her weight. She may have strapped herself into a girdle or other paraphernalia for maximum visual effect, but that didn’t alter the fact that her wiggle was tight and cute. In fact, it turned me on. She was my kind of chubby.”

She was chubby and attractive. It wasn’t ideal representation, not by a long shot, but it was something in a land of so very little. The description was imperfect but refreshing. For a fantasy fan like me, finding a fat, attractive female character felt revolutionary. Maybe it hit hard because it was my first time. I was 19 when I read Hard-Boiled Wonderland, which means it took me almost 15 years to find an unconventionally attractive woman in a fantasy novel who was not a mother, villain, or whore. And I had to go speculative to get it.

An avid childhood reader, I grew up on a steady diet of sword-and-sorcery. This meant a parade of maidens that were comely and lissome, which is fantasy slang for pretty and thin. I was really into the Forgotten Realms series for awhile—I’d buy as many as I could carry at Half-Price Books, and settle in with descriptions like this, from Streams of Silver (Part 2 of the Icewind Dale trilogy):

“Beautiful women were a rarity in this remote setting, and this young woman was indeed the exception. Shiny auburn locks danced gaily about her shoulders, the intense sparkle of her dark blue eyes enough to bind any man hopelessly within their depths. Her name, the assassin had learned, was Catti-brie.”

As our heroes journey a little further, they encounter a woman of easy virtue. She is described this way:

“Regis recognized trouble in the form of a woman sauntering toward them. Not a young woman, and with the haggard appearance all too familiar on the dockside, but her gown, quite revealing in every place that a lady’s gown should not be, hid all her physical flaws behind a barrage of suggestions.”

In the land of the dark elf Drizz’t do Urden, not only are good women beautiful, plain women are bad. They are beyond bad—they are pitiable. To be physically imperfect, overtly sexual, middle-aged is to be ghastly, horrid, wrong. Streams of Silver feels dated, but it was published in 1989. It’s a relatively recent entry in a long, sexist tradition of fantasy literature describing women in specific physical ways, with attributes that correlate to the way they look. To be fair to fantasy literature — more fair than they often are to the women in their pages — not all bad women are unattractive and not all good women are beautiful. But it is the case more often than not. Or to be more accurate, it is rare to find a woman important to the plot whose appearance isn’t a big if not key part of her character. Look at Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Once and Future King. I love these books. They are by and large populated by beautiful and unattractive women: women for whom appearance is the focal point. There are few plain or average or even quirky-cute Janes to be found.

Of course, there have always been exceptions: Dr. Susan Calvin in Asimov’s Robot series. Meg in A Wrinkle in Time. The Chubby Girl in Hard-boiled Wonderland (I’d like to note that everyone in the book is described as an archetype, not a name, but also, couldn’t you have called her Attractive Girl or Young Woman or the patriarchal but still less appearance-focused Scientist’s Daughter? I mean, damn). But although there are outliers, the legacy of women’s appearance as paramount quality is a pervasive one. It is getting better, in big and important ways. But beautiful, white, thin, symmetrical, straight, cis women still rule the realms of magic. Within the genre, women’s physical appearance remains a tacitly acceptable bastion of sexism and often racism.

This was a hard pill to swallow because growing up, fantasy was my escape and my delight. It was tough to see that my sanctuary was poisoned. It took me a while to see it. Probably because I’m privileged—my hair looks like spun straw, my skin glows like a plastic bag, and my body shape is somewhere between elf and hobbit—and possibly because like a lot of people who enjoy sword-and-sorcery, I was used to the paradigm of Nerds Against Jocks, Nerds Against Hot Girls, Nerds Against the World. I thought what I loved could never do me wrong, except it did. Like many women, I have a socially acceptable amount of body dysmorphia, which is a fancy way of saying I don’t think I can ever be too pretty or too thin. I don’t actually believe I’m worthless because I’m not the fairest in the land, but there’s a mental undercurrent I don’t know if I’ll ever truly shake. And I don’t solely blame Tolkien for every time I’ve scowled at a mirror, but reading about how “The hair of the Lady was of deep gold… but no sign of age was upon them” is enough to make you reach for the bleach and retinol, trying forever to reach an unattainable Galadriel standard.

Recognizing that fantasy fiction was just as bad as mainstream culture was a cold shower, made icier by the realization that not all fantasy fans agreed. Quite the opposite, in fact: as the Internet grew and nerd culture found many new digital homes, I began to see a smug fan base: people who believed that nerd culture was not only victimized, but a more enlightened tribe than the mainstream masses.

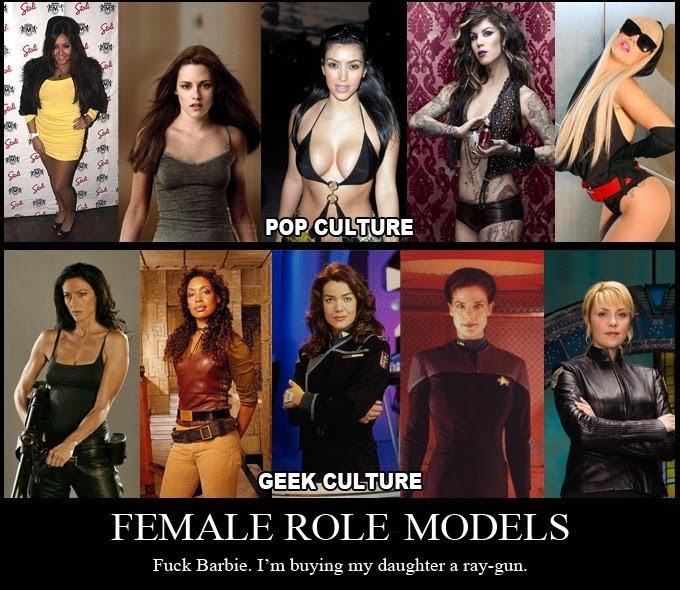

This attitude was captured well in the Female Role Models meme:

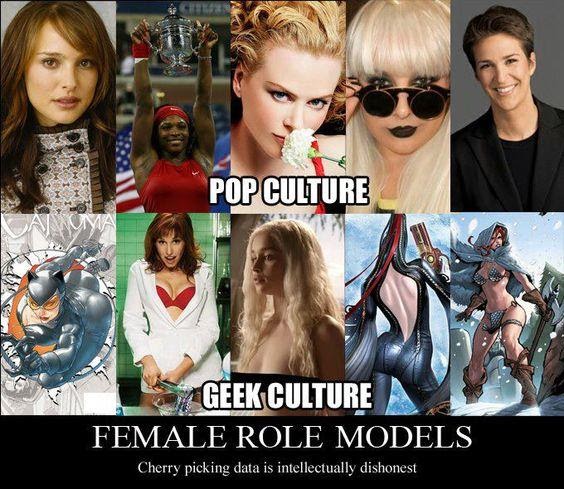

A counter-meme sprung up, pointing out the hypocrisy of the statement:

But the original meme had already circulated, and the thinking behind it was far from over. Treating geek culture as unimpeachable is not only dishonest—it’s dangerous. Look at GamerGate, where game developers Zoë Quinn and Brianna Wu and feminist media critic Anita Sarkeesian received doxing, threats of rape, and death threats, for having opinions about a piece of media. Look at the Fake Geek Girl meme. Look at the backlash to a rebooted Ghostbusters. I don’t even want to talk about Star Wars, but look at Star Wars’ fans reaction to the character of Rose Tico. The list goes on and on, and the message is consistent: women should look and act a certain way, and woe betide anyone who falls out of line.

Is the next step to treat fantasy like the ruined woman from Streams of Silver, forsaking it forever and banishing it to the realms of Things We Don’t Read Anymore? Absolutely not. That’s throwing a magical, beloved baby out with the sexist bathwater. Genre doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it’s forever shifting and hopefully evolving, always informed by the humans that create it. It can be taken back and forward and out and around. And thoughtful female characters in fantasy don’t end with A Wrinkle in Time’s Meg Murry. Take Cimorene from Patricia C. Wrede’s Dealing with Dragons: she’s tall and dark-haired, a departure from her petite, blonde princess sisters, but her most notable attributes are her sense of adventure and independence. She goes on to buddy up with a dragon, Kazul, as well as another princess, Alianora, who is “slender with blue eyes and hair the color of ripe apricots.” Their friendship shows that it’s not about being blonde and slim, dark-haired and tall, or having three horns, green scales with gray edges, and green-gold eyes: it’s that archaic gender norms are limiting and meaningless.

More recently, Valentine DiGriz from Ferrett Steinmetz’s Flex is overweight, attractive, and wryly aware of both. Not long after she’s introduced, she quips, “Is there a word that means ‘pretty’ and ‘dumpy’ at the same time? Hope not. Somebody’d use it to describe me.” This echoes the first reference to her physicality: “She bent over to pick up a large-cupped foam bra, then yanked off her shirt. Paul saw her ample breasts pop out before he averted his eyes.” Though busty and funny, Valentine’s not a funny fat friend trope: she likes to get laid and isn’t shy about it. Beyond all that, she’s an ace videogamemancer who often steps in to save the day.

Sometimes appearance is more key to a character, like in the case of Sunny Nwazue of Nnedi Okorafor’s Akata Witch: “I have West African features, like my mother, but while the rest of my family is dark brown, I’ve got light yellow hair, skin the color of ‘sour milk’ (or so stupid people like to tell me), and hazel eyes that look like God ran out of the right color.” Oh, and Sunny is magical and needs to help capture a serial killer. No big deal.

There are more: Scott Lynch’s The Lies of Locke Lamora. Emma Bull’s War for the Oaks. Noelle Stevenson’s graphic novel Nimona. Anything and everything by Kelly Link or Angela Carter. The point is not that the women in these books are beautiful or unattractive, or even that the way they look isn’t memorable or part of the plot. They have bodies and faces, but a wasp waist or plain face isn’t a beeline to the contents of their souls or significance in the story. Their attributes aren’t code for good or evil, and never all that they are. Physical appearance is one part of a layered, multi-faceted character, because women are human beings, not tired tropes or misogynist fantasies.

Exploring texts where women are treated as fully rounded characters is a great place to start dismantling some of fantasy’s baggage. Reading stuff that’s sexist is good too: it’s important to see it and recognize it for what it is (Peter Pan has interesting ideas and so many problems). Read everything and understand that fantasy is not a pristine chalice in an airless chamber, ready to break at the slightest shift in the atmosphere. It’s raw and powerful and wild, the provenance of old creatures and new gods and spells that can take out continents. Sidelining women through the way they look is definitely the way things often are, but don’t have to be. I can think of few genres better suited to tell stories of a more beautiful world.

Rosamund Lannin reads and writes in Chicago for publications like Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and Vice. You can find her on the Internet @rosamund, or anywhere magic and reality hold hands.